Makeup Sells and Brain Cells Don’t. Just ask Henrietta Lacks. Oh wait!Why PCOS Is Just a Game of Numbers and Damn Your Life, Damn Your Health

They turned PCOS into vanity while it rewires your brain. Acne sells, eggs sell, and bodies sell, but your memory, focus, and sanity don’t make the market.

The Setup: The Cosmetic Lie

Doctors strip Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS) of its neurological weight when they call it cosmetic. They reduce it to “extra hair,” acne, or infertility and erase the fatigue, memory lapses, depression, and brain fog that wreck daily life. That language isn’t neutral. It shields insurers from paying claims, funnels Black women into beauty aisles, and keeps pharmaceutical companies from investing in neurological research.

PCOS affects 5–10% of women worldwide (Azziz et al., 2016). Black women live with the compounding weight of racism and sexism in medicine, and when we present with symptoms that cut into our focus or mood, doctors code them as vanity. That dismissal doesn’t describe PCOS; it protects profit.

The Neurological Theft

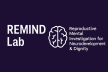

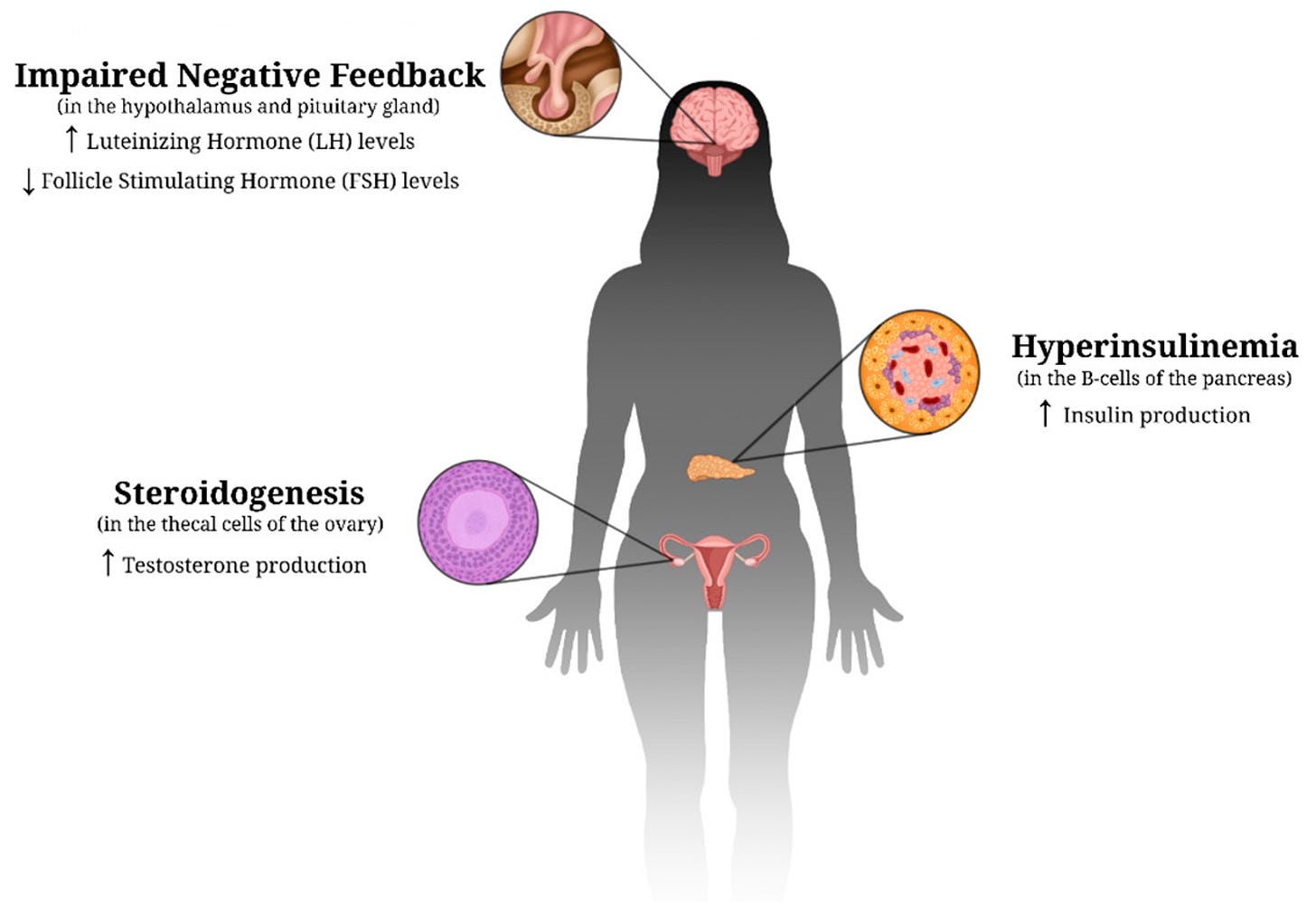

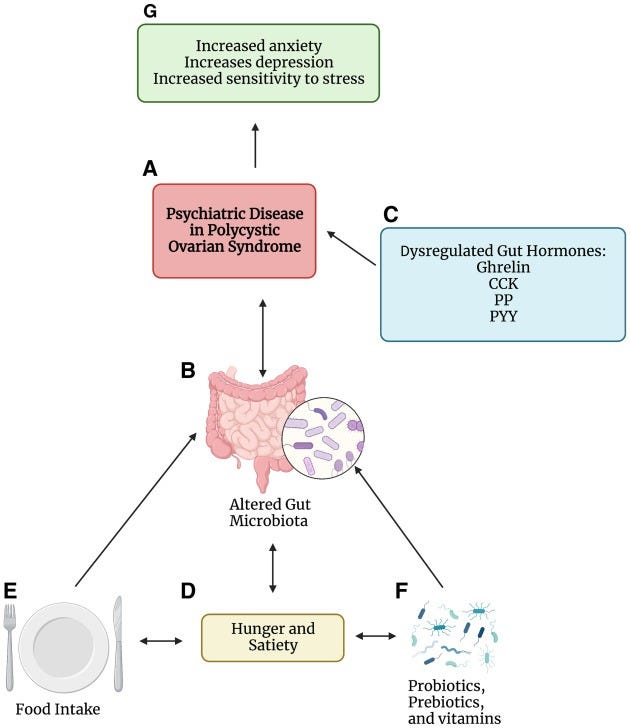

PCOS doesn’t just sit in the ovaries. It destabilizes the brain. Researchers have documented structural differences in the hippocampus and frontal cortex regions that govern memory, mood, and executive function (Cooney et al., 2020). Women with PCOS show measurable deficits in memory and attention (Barry et al., 2011) and face sharply higher risks of depression, anxiety, and psychiatric disorders (Brutocao et al., 2018).

Doctors often reframe these neurological changes as personality flaws. When dopamine disruption blocks focus, Black women hear they’re lazy. When serotonin imbalance drives irritability, they become aggressive. When gray matter changes weaken memory, they tend to listen less when they’re stressed or inattentive. PCOS robs women of neurological stability, and medicine blames us for the theft.

The disorder also assaults mental health through stigma. Elevated androgen levels heighten anxiety and depression (Balıkçı et al., 2014; Hussain et al., 2015). Physical markers like acne, hirsutism, and weight struggles drag women into social isolation, body dissatisfaction, and diminished self-esteem (Bachega et al., 2023; Snyder, 2006; Zaman et al., 2023). Women often describe feeling “different” from peers because society links femininity to smooth skin, thin bodies, and “acceptable” hair. The cosmetic industry weaponizes that difference.

Researchers now agree: PCOS is a complex disorder with reproductive, metabolic, and profound psychological implications. It influences mood, cognition, and overall quality of life (Almhmoud et al., 2024; Norman & Teede, 2018). Ignoring the neurological and psychological weight of this disorder doesn’t just fail women; it commodifies them.

Who Profits From the Cosmetic Frame?

Corporations turn cosmetic framing into a business model.

Pharmaceutical companies lock PCOS inside the fertility box. They market birth control, IVF, and egg-freezing while avoiding costly neurological research (Palomba et al., 2015). They push weight-loss drugs like Ozempic as one-size-fits-all solutions, even though GLP-1s do nothing for neurological decline (Rubino et al., 2022).

The beauty and wellness industries often exploit stigma. They sell laser treatments, acne serums, diet teas, and skin procedures to women desperate to erase visible markers of PCOS. Dermatologic symptoms associated with androgens can become endless profit streams (Ach & Feryel, 2024; Tomlinson et al., 2017). Geller et al. (2011) demonstrated how markets intentionally divert women toward cosmetic fixes rather than advocating for systemic care.

Insurance companies save billions by hiding behind the cosmetic label. They deny neuroimaging, block therapy tied to PCOS, and resist long-term hormonal monitoring. Dewani et al. (2023) traced how these denials shift costs to patients and keep women trapped in a cycle of consumerism.

Every time medicine calls PCOS cosmetic, insurers protect margins, pharma companies expand markets, and the beauty industry fattens its bottom line. Black women pay a high price in terms of memory, focus, and stability.

The Unanswered Question

If science proves that PCOS alters neurotransmitters, shrinks gray matter, and wrecks quality of life, why do doctors still call it cosmetic?

Because cosmetics equal control, cosmetics build markets. Cosmetic lets insurers avoid accountability. Cosmetics protect industries that already profit from stigma.

And when Black women lose memory, clarity, and cognitive health, medicine shrugs. That erasure isn’t accidental. It echoes a century-long pattern from Stevens’s 1913 lie that Black women don’t feel pain to the ongoing exclusion of mental health from maternal mortality rates. Calling PCOS cosmetic continues a tradition of monetizing Black women’s neglect.

Call to Action

This is Zsanine for REMIND Lab... remember….

PCOS is neurological. When doctors label it cosmetic, they protect insurers, boost pharma profits, and hand our bodies to the beauty industry. That framing is not ignorance; it is strategy. Until we rip away the cosmetic mask, Black women will keep paying the price with our minds.

References

Ach, T., & Feryel, A. (2024). Deciphering the role of androgen in the dermatologic manifestations of polycystic ovary syndrome patients: A state-of-the-art review. Diagnostics, 14(22), 2578. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics14222578

Almhmoud, H., Alatassi, L., Baddoura, M., Sandouk, J., Alkayali, M., Najjar, H., … & Zaino, B. (2024). Polycystic ovary syndrome and its multidimensional impacts on women’s mental health: A narrative review. Medicine, 103(25), e38647. https://doi.org/10.1097/md.0000000000038647

Azziz, R., Carmina, E., Chen, Z., Dunaif, A., Laven, J. S. E., Legro, R. S., & Lizneva, D. (2016). Polycystic ovary syndrome. Nature Reviews Disease Primers, 2, 16057. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrdp.2016.57

Bachega, F., Baracat, M., Simões, R., Maciel, G., Lobo, R., Soares, J., … & Baracat, E. (2023). New comprehension on polycystic ovary syndrome and sexual function: A systematic review and meta-analysis. https://doi.org/10.20944/preprints202309.1520.v1

Balıkçı, A., Erdem, M., Keskin, U., Zincir, S., Gülsün, M., Özçelik, F., … & Ergün, A. (2014). Depression, anxiety, and anger in patients with polycystic ovary syndrome. Nöro Psikiyatri Arşivi, 51(4), 328–333. https://doi.org/10.5152/npa.2014.6898

Barry, J. A., Hardiman, P. J., & Saxby, B. K. (2011). Cognitive functioning in polycystic ovary syndrome. Human Reproduction, 26(9), 2462–2468. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/der222

Bazmi, S., Sepehrinia, M., Pourmontaseri, H., Bazyar, H., Vahid, F., Farjam, M., … & Shakouri, N. (2024). Androgenic alopecia is associated with a higher dietary inflammatory index and a lower antioxidant index score. Frontiers in Nutrition, 11, 1433962. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2024.1433962

Brutocao, C., Zaiem, F., Alsawas, M., Morrow, A. S., Murad, M. H., & Javed, A. (2018). Psychiatric disorders in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Endocrine, 62(2), 318–325. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12020-018-1692-3

Cooney, L. G., Lee, I., Sammel, M. D., Dokras, A., & Allison, K. C. (2020). Brain structural differences in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: A VBM study. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 113, 104544. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2019.104544

Dewani, D., Karwade, P., & Mahajan, K. (2023). The invisible struggle: The psychosocial aspects of polycystic ovary syndrome. Cureus, 15(12), e51321. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.51321

Geller, D., Pacaud, D., Gordon, C., & Misra, M. (2011). State-of-the-art review: Emerging therapies: The use of insulin sensitizers in the treatment of adolescents with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). International Journal of Pediatric Endocrinology, 2011(1), 9. https://doi.org/10.1186/1687-9856-2011-9

Hussain, A., Chandel, R., Ganie, M., Dar, M., Rather, Y., Wani, Z., … & Shah, M. (2015). Prevalence of psychiatric disorders in patients with a diagnosis of polycystic ovary syndrome in Kashmir. Indian Journal of Psychological Medicine, 37(1), 66–70. https://doi.org/10.4103/0253-7176.150822

Kim, Y., Chae, K., Kim, S., Kang, S., Yoon, H., & Namkung, J. (2025). Risk of mental disorders in polycystic ovary syndrome: Retrospective cohort study of a Korean nationwide population-based cohort. International Journal of Women’s Health, 17, 627–638. https://doi.org/10.2147/ijwh.s490673

Moghadam, Z., Fereidooni, B., Saffari, M., & Montazeri, A. (2018). Polycystic ovary syndrome and its impact on Iranian women’s quality of life: A population-based study. BMC Women’s Health, 18, 65. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-018-0658-1

Norman, R., & Teede, H. (2018). A new evidence‐based guideline for assessment and management of polycystic ovary syndrome. The Medical Journal of Australia, 209(7), 299–300. https://doi.org/10.5694/mja18.00635

Palomba, S., Santagni, S., Falbo, A., & La Sala, G. B. (2015). Complications and challenges associated with polycystic ovary syndrome: Current perspectives. International Journal of Women’s Health, 7, 745–763. https://doi.org/10.2147/IJWH.S70314

Rubino, D. M., Greenway, F. L., Khalid, U., O’Neil, P. M., Rosenstock, J., Sørrig, R., & Garvey, W. T. (2022). Effect of weekly subcutaneous semaglutide vs placebo as an adjunct to intensive behavioral therapy on weight loss in adults with overweight or obesity. JAMA, 327(2), 138–150. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2021.23619

Snyder, B. (2006). The lived experience of women diagnosed with polycystic ovary syndrome. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic & Neonatal Nursing, 35(3), 385–392. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1552-6909.2006.00047.x

Tomlinson, J., Pinkney, J., Adams, L., Stenhouse, E., Bendall, A., Corrigan, O., … & Letherby, G. (2017). The diagnosis and lived experience of polycystic ovary syndrome: A qualitative study. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 73(10), 2318–2326. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.13300

Zaman, S., Yunus, S., Noor, K., Asif, U., Hayat, R., Raana, G., … & Khan, M. (2023). Assessment of body image distress in women with polycystic ovarian syndrome. PJMHS, 17(4), 299–302. https://doi.org/10.53350/pjmhs2023174299