Do We Even Know What Dementia Really Is?

Because not every kind of memory loss is Alzheimer’s and not every diagnosis tells the truth.

Every time we hear “dementia,” most of us automatically think Alzheimer’s. But that’s only one piece of the story. There are several kinds of dementia, and understanding which one is showing up can be the difference between getting help early and being brushed off until it’s too late.

And for Black women who are still told “you’re stressed” instead of “let’s run a cognitive screen,” that difference matters even more. So let’s slow this down together. Grab your tea, your matcha, your brunch plate, whatever you need. Let’s walk through what’s really going on inside the brain when we talk about dementia.

Dementia Isn’t One Disease: It’s a Whole Neighborhood

Think of dementia like a neighborhood. Alzheimer’s is the biggest house on the block, but it’s not the only one there. “Dementia” isn’t a diagnosis; it’s a term for when memory, reasoning, or daily functioning start breaking down due to more profound changes in the brain. Researchers like James and Bennett remind us that dementia is a syndrome, a set of symptoms that can come from several different diseases. Some start with blood flow issues, some with protein buildup, and others from years of trauma or inflammation. And do you know what the sad truth is? Not every doctor knows which house you’re standing in. A global review found that even trained clinicians disagree on dementia diagnoses. That’s how fuzzy and biased the process still is.

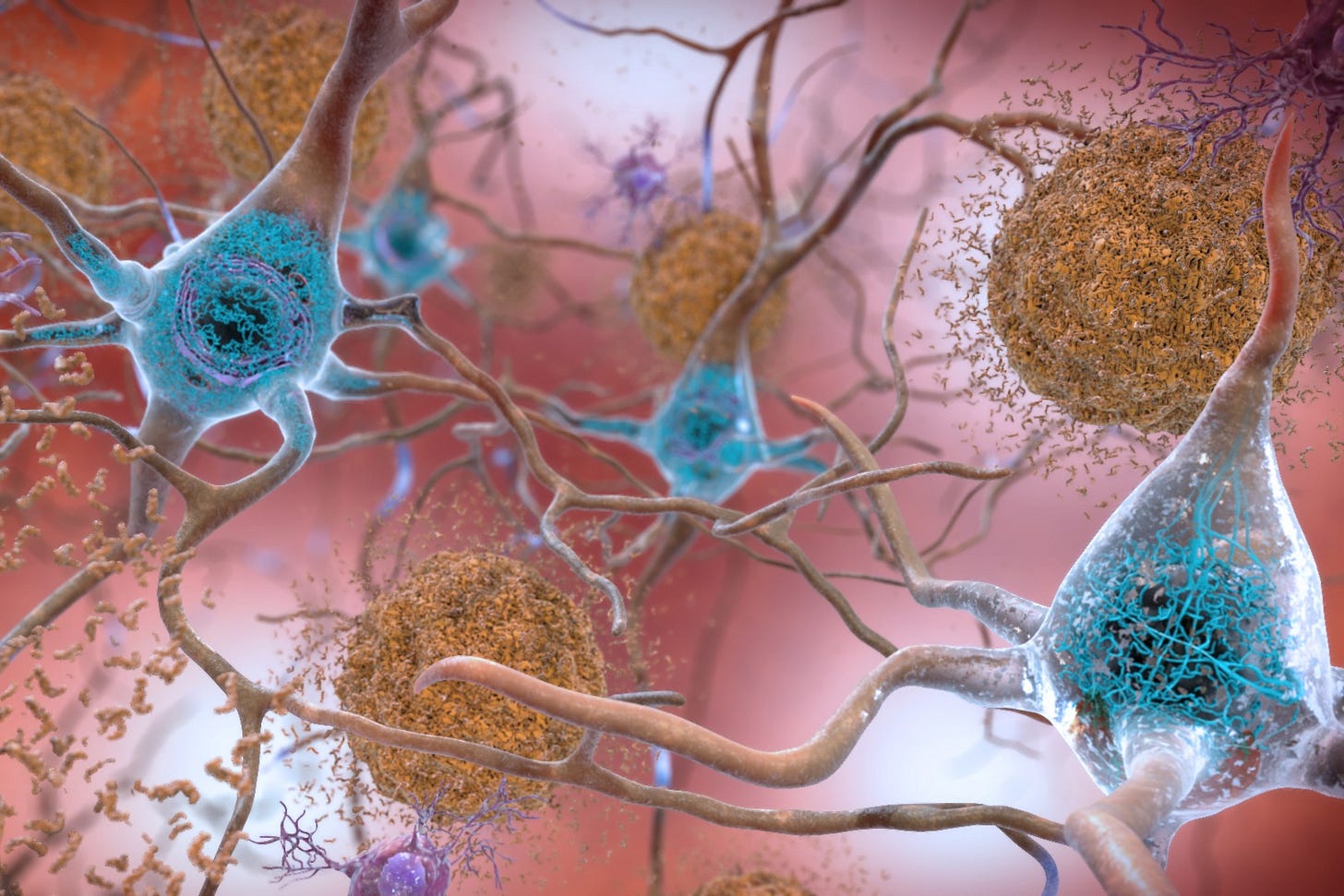

Alzheimer’s Disease: the One Everyone Talks About

This is the most common form. Under a microscope, you’d see sticky clumps called amyloid plaques and twisted fibers known as tau tangles. They choke off neurons, starting in the hippocampus (where memory lives) and spreading outward. So first it’s short-term memory. Then it’s decision-making. Eventually, it’s speech and personality. But Alzheimer’s doesn’t look the same in every brain. Black women often experience mixed dementia. Alzheimer’s changes are mixed with blood flow problems. When multiple processes overlap, the brain deteriorates faster. It’s like several fires burning at once.

Vascular Dementia: the One Hiding in Plain Sight

This one often follows strokes, hypertension, or anything that messes with blood flow. It’s also one of the biggest reasons Black women get diagnosed late or misdiagnosed altogether. Our blood pressure, our pregnancies, our stress, all of it affects our vascular health. When small vessels clog or burst, brain cells suffocate. The result? Memory lapses, confusion, mood swings. The hardest part? It’s preventable!!

So what that means is that if it is caught early, it can be stopped!

Managing blood pressure, sleep, and stress can help slow it down. But that requires doctors who take our symptoms seriously, and too many still don’t.

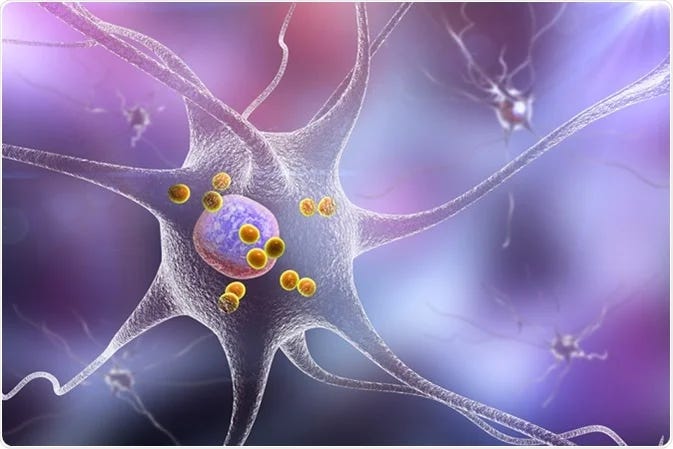

Lewy Body Dementia: the Misunderstood One

This one is tricky. It comes with hallucinations, movement issues, and sudden shifts in alertness. It’s caused by clumping of a protein called alpha-synuclein inside neurons. Doctors often mistake it for depression or “just aging.” That’s why so many Black families say, “Mama started seeing things” or “She’s just not herself lately,” and no one connects it to Lewy body dementia until years later. This type reminds us that sometimes what looks “spiritual” or “emotional” in our families might actually be neurological.

Frontotemporal Dementia: the One That Looks Emotional Before It Looks Medical

This one hits the front and side parts of the brain that control language and personality. People may become impulsive, withdrawn, or start saying things that feel “out of character.” For Black women, that’s often labeled as “attitude” or “burnout.” Rarely do we hear a doctor say, “Let’s check her frontal lobe.” Frontotemporal dementia teaches us something powerful. When our personalities shift, it’s not always emotional; it might be neurological.

Mixed Dementia: the One Most of Us Actually Have

Most people, especially later in life, don’t have a single precise diagnosis. They have a blend: Alzheimer’s plus vascular disease, sometimes with Lewy bodies mixed in. That overlap speeds things up. It makes symptoms blur together, and it makes diagnosis harder, especially for Black patients who are already under-tested and under-imaged. This is where brain scans matter. Structural MRI can help distinguish, but access to imaging remains a privilege. Too many of us never even get the scan.

A Little History, Because the Ancestors Already Knew

Centuries before brain scans, the Persian physician Avicenna (980–1037 CE) described dementia as “a loss of intellect due to moisture and heat in the brain.” He didn’t have modern tools. He just observed patterns. And that’s what we’ve always done too. Watched our elders, noticed shifts, and tracked changes. We’ve always been our own data.

So What Do We Do With This?

We learn the language before we’re forced to speak it. We pay attention to speech, mood, sleep, and balance. We ask for specific tests: cognitive screens, sleep studies, and neuroimaging when possible. And we stop letting “just tired” or “just stress” be the final answer. Because “forgetfulness” isn’t always harmless, it can be the first whisper of something bigger. And we deserve doctors who don’t shrug off those whispers.

Next week, we’re breaking down what prevention really looks like when it’s personalized for us because dementia isn’t inevitable, and neither is being ignored.

References

Cerullo, E. et al. (2021). Interrater agreement in dementia diagnosis: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 36(8), 1127–1147.

Clinton, L. et al. (2010). Synergistic interactions between Aβ, tau, and α-synuclein. Journal of Neuroscience, 30(21), 7281–7289.

Gustavsson, A. et al. (2022). Global estimates on the number of persons across the Alzheimer’s disease continuum. Alzheimer’s & Dementia, 19(2), 658–670.

James, B. & Bennett, D. (2019). Causes and patterns of dementia: an update in the era of redefining Alzheimer’s disease. Annual Review of Public Health, 40(1), 65–84.

Kelly, M. et al. (2022). Applying diagnostic criteria for dementia with Lewy bodies. Alzheimer Disease & Associated Disorders, 37(1), 88–91.

Persson, K. et al. (2016). Fully automated structural MRI in clinical dementia workup. Acta Radiologica, 58(6), 740–747.

Rasquin, S. et al. (2005). Effect of diagnostic criteria on post-stroke dementia prevalence. Neuroepidemiology, 24(4), 189–195.

Taheri-Targhi, S. et al. (2019). Avicenna and his early description and classification of dementia. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease, 71(4), 1093–1098.

Tartaglia, M. et al. (2011). Neuroimaging in dementia. Neurotherapeutics, 8(1), 82–92.

Younes, K. et al. (2018). Auto-antibodies mimicking frontotemporal dementia. SAGE Open Medical Case Reports, 6.